- Blinded Flight

- Overview

- Light Pollution

- Collisions

- Collisions Research

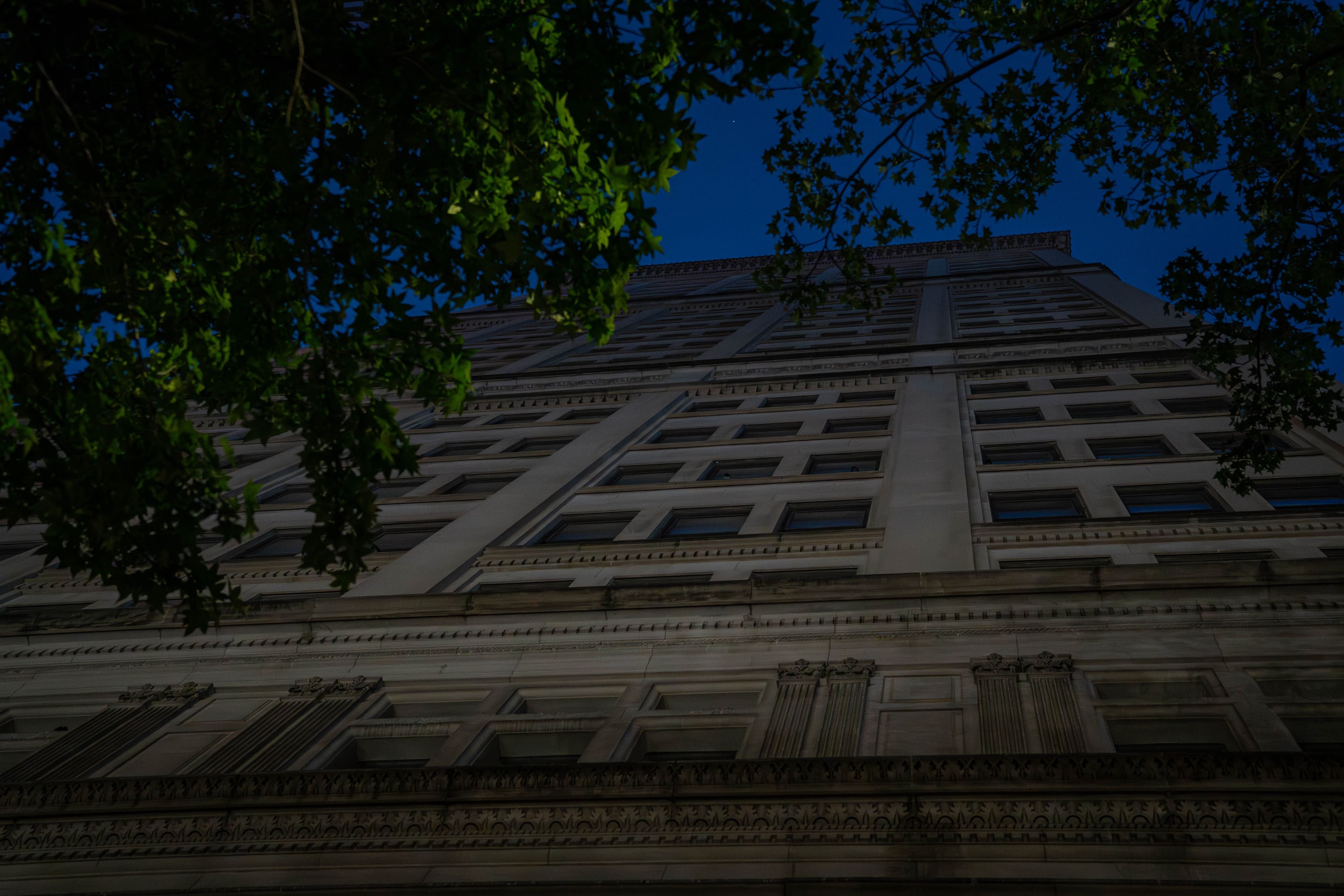

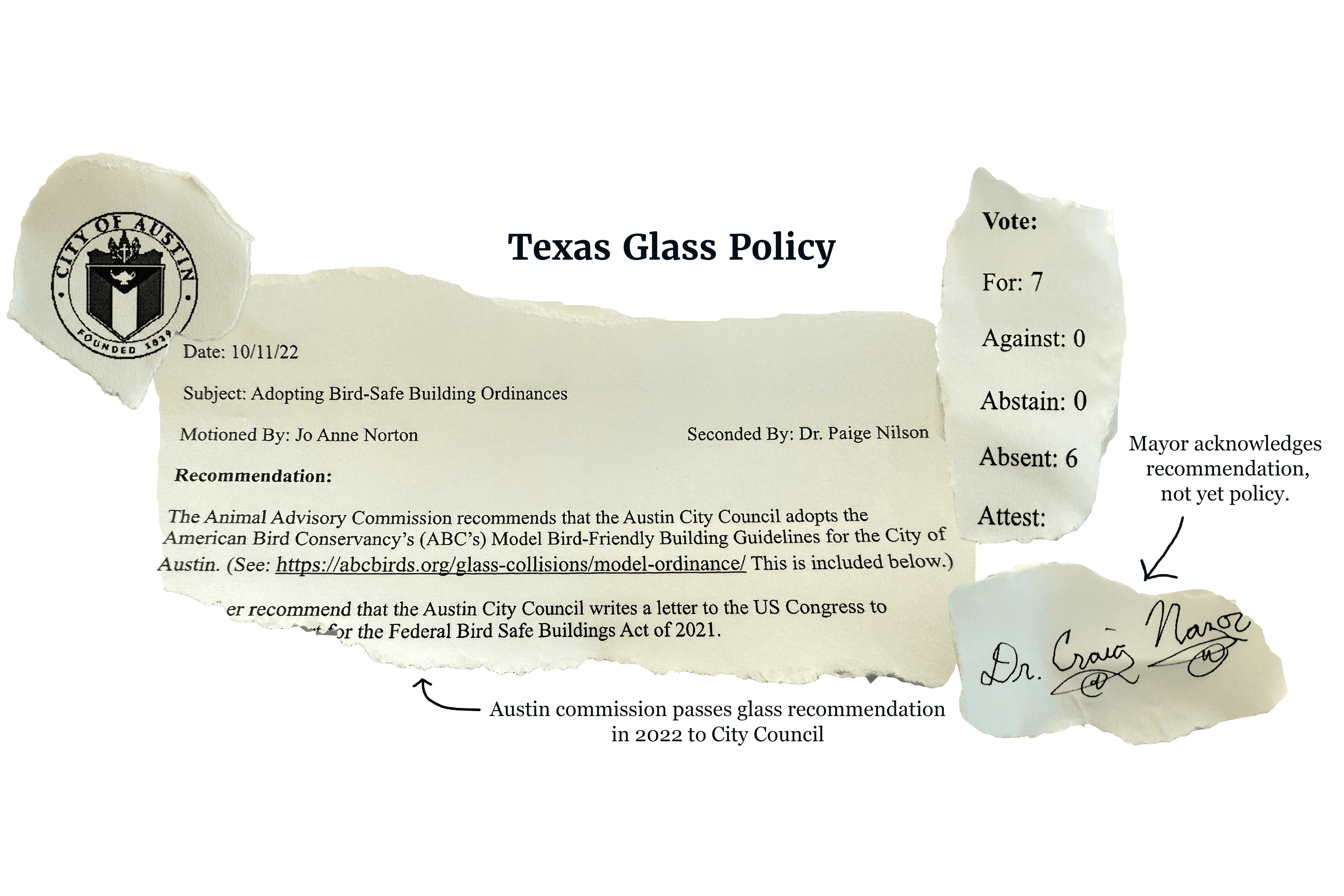

- Policy

- Glass Research

- Architecture

- Enthusiasts

- The Bottom Line

- About

- Further Resources

Blinded Flight

Scroll right to read story

Overview

In 2014, Scott R. Loss et al. published a landmark study in The Condor estimating that 365 to 988 million birds are killed annually in the U.S. due to building collisions, with light pollution playing a significant role. The study noted that "migratory species are attracted to large lighted buildings during their nocturnal migration; as birds either immediately collide with lighted buildings or become entrapped before later dying of collision or exhaustion." Localized studies, such as one conducted in Minneapolis in 2019, offer valuable context. This research recorded 768 bird collisions across 48 building façades (0–194 collisions per façade) and found both lighting area (total illuminated surface) and lighting proportion (percentage of façade illuminated) to be significant predictors of collision rates. Statistical analysis confirmed a 99% likelihood that these factors are linked to collision rates, further highlighting the strong connection between artificial light and bird collisions.

While the exact number of bird deaths attributable to light pollution remains uncertain on a macro-scale, individual insights offer vital clues. Localized research, like that from Minneapolis, has grown in prominence in recent years in cities such as Dallas and College Station, Texas; Ithaca and New York, New York; and Rector, Pennsylvania, transforming what was once solely a scientific concern into a multifaceted issue now addressed by policymakers, architects, and even enthusiasts. Blinded Flight delves into these microcosms of discovery, uncovering key narratives within the interconnected worlds of research, policy, design, and advocacy. Through on-the-ground reporting and expert insights, Blinded Flight weaves together a broader narrative of how artificial light and building collisions disrupt migratory birds and highlights practical solutions to mitigate their combined impact.

“We share this planet with millions of species that need us, and we need them. Expanding our idea of our place in the world is critical— not just for birds but for humanity.”

“First, light pollution from miles away draws birds into urban areas, disrupting their natural migration paths and behaviors. Second, birds take shelter in urban vegetation such as trees or shrubs. When greenery is scarce they rely on man-made structures like ledges and rooftops. Third, reflective glass windows lead to fatal collisions.”

Light Pollution

Light pollution has a significant impact on our planet, with over 80% of people in the U.S. and Europe living under artificially brightened skies, according to the New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness (2016). Although urban areas cover only a small portion of land, they produce a disproportionate amount of light, exposing birds to 24 times more artificial light than the national average, according to the study Bright Lights in the Big Cities: Migratory Birds’ Exposure to Artificial Light (2019). The majority of North America's migratory birds are nocturnal migrants, and two and a half to five billion birds migrate through the United States at night annually (Dokter et al., 2018). Skyglow—the hazy glow over cities—strongly influences where migratory birds stop to rest during their long journeys. As Andrew Farnsworth, a visiting scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, notes, “The pattern of attraction we see in birds near artificial light is striking—they slow down, circle, and fail to reorient until the lights are turned off.” In key migration paths like the western flyway, skyglow is the single strongest factor determining where birds choose to rest. Experimental evidence supporting this conclusion includes both traditional field observations and advanced remote sensing technologies, such as radar.

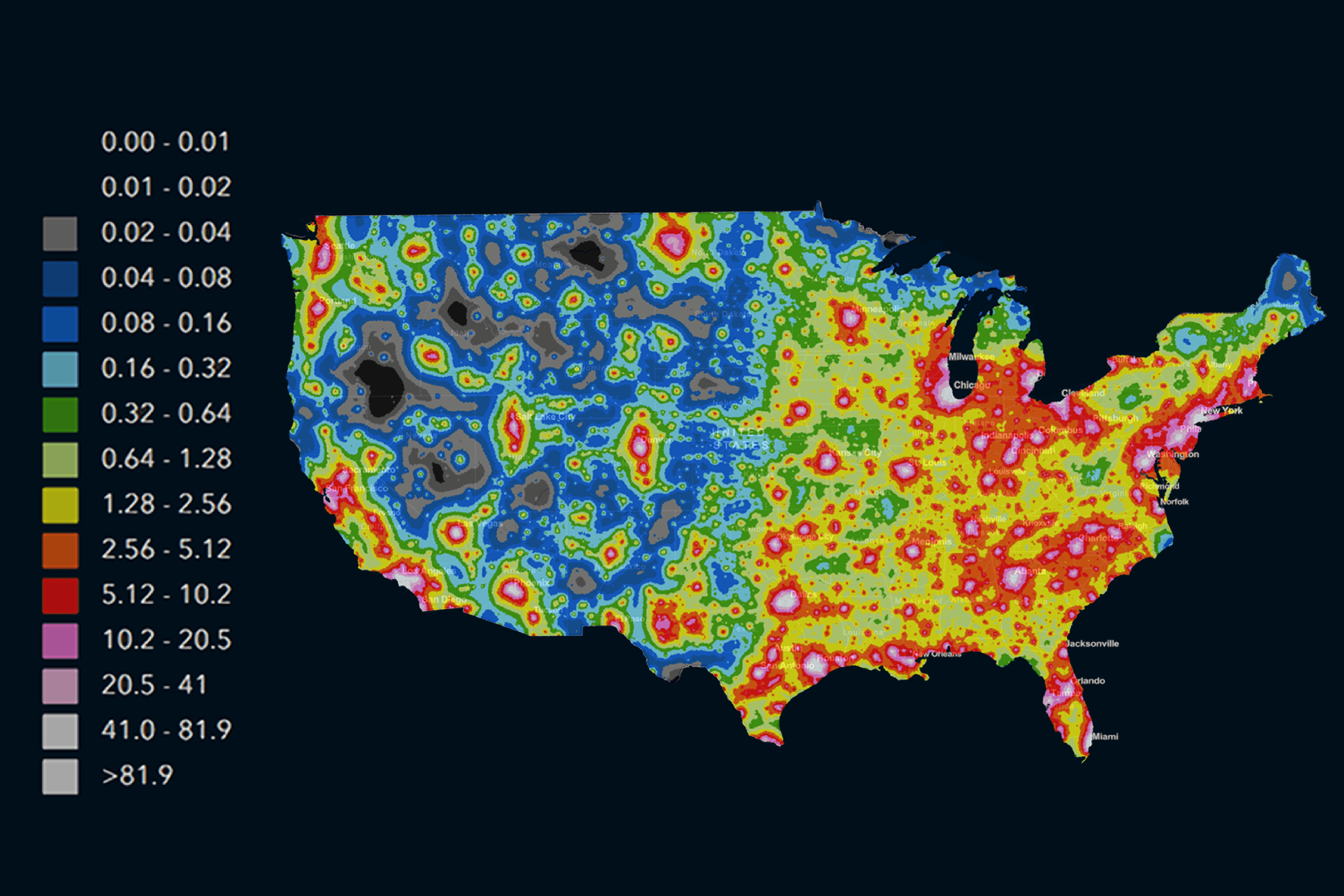

This light pollution map of the United States, shows the intensity of artificial light across the country, measured as a ratio to natural background light. The colors range from black (least light pollution) to bright red and ultimately white (most intense), illustrating how densely populated areas—particularly in the eastern U.S.—experience significant "skyglow." This artificial light obscures the night sky, impacting nocturnal wildlife, including 80% of migratory birds who rely on natural darkness for navigation.

Night Sky Risk Map

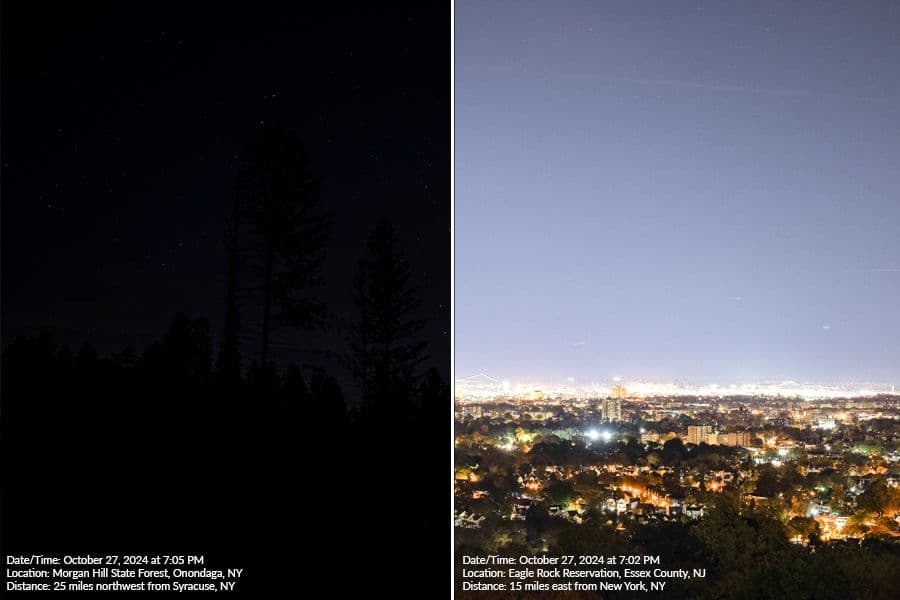

The National Park Service's Night Sky Risk Map, when zoomed in closer, highlights Morgan Hill State Forest near Syracuse, NY, and Eagle Rock Reservation in New Jersey near New York City, showcasing the stark contrast between relatively dark areas and regions heavily impacted by light pollution. Notice how the dense light pollution surrounding New York City encroaches on nearby natural areas, illustrating the challenges of preserving dark skies in urbanized regions.

“Map of Sensory Pollution Risks across the Contiguous United States.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, irma.nps.gov/NSNSD/RiskMap/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2024.

Night Sky Comparison

To better understand the visual impact of light pollution, this side-by-side comparison—both images captured within the same time frame and with identical exposure settings (f/5.6)—reveals its profound effect on the night sky. Exposure refers to how much light is allowed into the camera to create an image, ensuring both scenes are directly comparable. On the left, the clear, star-filled sky over Morgan Hill State Forest in Onondaga, NY, just 25 miles from Syracuse, showcases a natural, unpolluted nightscape. In stark contrast, the image on the right, taken from Eagle Rock Reservation in Essex County, NJ, just 15 miles from New York City, highlights the overwhelming effect of skyglow. Skyglow disrupts birds’ natural navigation systems, drawing them into urban areas and creating an ecological trap.

“In 2010. That’s when we began the lights-on/lights-off experiments. The results showed this pattern of attraction: birds were aggregating, circling, and slowing down, staying very close to the light and not moving in direct lines as they normally would. That same behavior could be recreated in simulations, giving us confidence in understanding what’s happening in the real world.”

In 2010, ornithologists seized a unique opportunity to study the effects of artificial light on birds by utilizing New York City's Tribute in Light (TiL) art installation, an annual event held atop the Battery Parking Garage. Since its inception in 2002, observers had noted that birds, drawn to the powerful beams (approximately 44 billion candela) like moths to a flame, would circle the lights in large numbers. Over seven years (2010–2017), researchers employed acoustic monitors and National Weather Service radar data to assess the birds' responses and later expanded their data set through computer simulations. The TiL art installation, which occurs for only one night annually, coincides with the fall migration season, spanning from late August to early November. “By summing the differences between bird numbers within 5 km of the installation and the expected baseline densities, we estimate that ≈1.1 million birds were affected by this single light source during our study period of seven nights over seven years,” report Benjamin Van Doren and colleagues.

BirdCast/Van Doren, Benjamin, and Farnsworth, Andrew. (2015). Birds Fly in Tribute in Light 4, 9/11/2015. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mk4yMOloCHc.

“You have to think about how to scale an experiment to the biology of how birds are behaving when they're migrating at night. How am I going to create an experiment that allows me to manipulate light yet study the organisms themselves as they behave both individually and across tens of kilometers? I do think that with some technological advances happening now—there's progress. The primary issue isn't a lack of interest—it's how to handle the logistics.”

Footage captured by a Forward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) camera at the Tribute in Light installation. These cameras detect heat in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum, allowing us to see what the eye cannot. What may appear as flecks of dust on the camera’s sensor are actually large swarms of birds drawn to the beams.

BirdCast/Van Doren, Benjamin, and Farnsworth, Andrew. (2015).

This radar animation shows bird density over Manhattan from the night of September 11 to the early morning of September 12, 2015. Warmer colors (yellow to red) represent higher bird densities, while cooler colors (blue to green) indicate lower densities. In the inset, the Tribute in Light symbol turns yellow when the lights are on and gray when the lights are off. The beams attract large numbers of birds, visible as intense red areas close to the installation.

BirdCast/Van Doren, Benjamin, and Farnsworth, Andrew. (2015). BirdCast.

“The Tribute in Light study is a great poster child for applying science to good conservation. There’s always more to learn about how long and how quickly turning off lights impacts birds positively, but continued research could lead to even more conservation action and better solutions.”

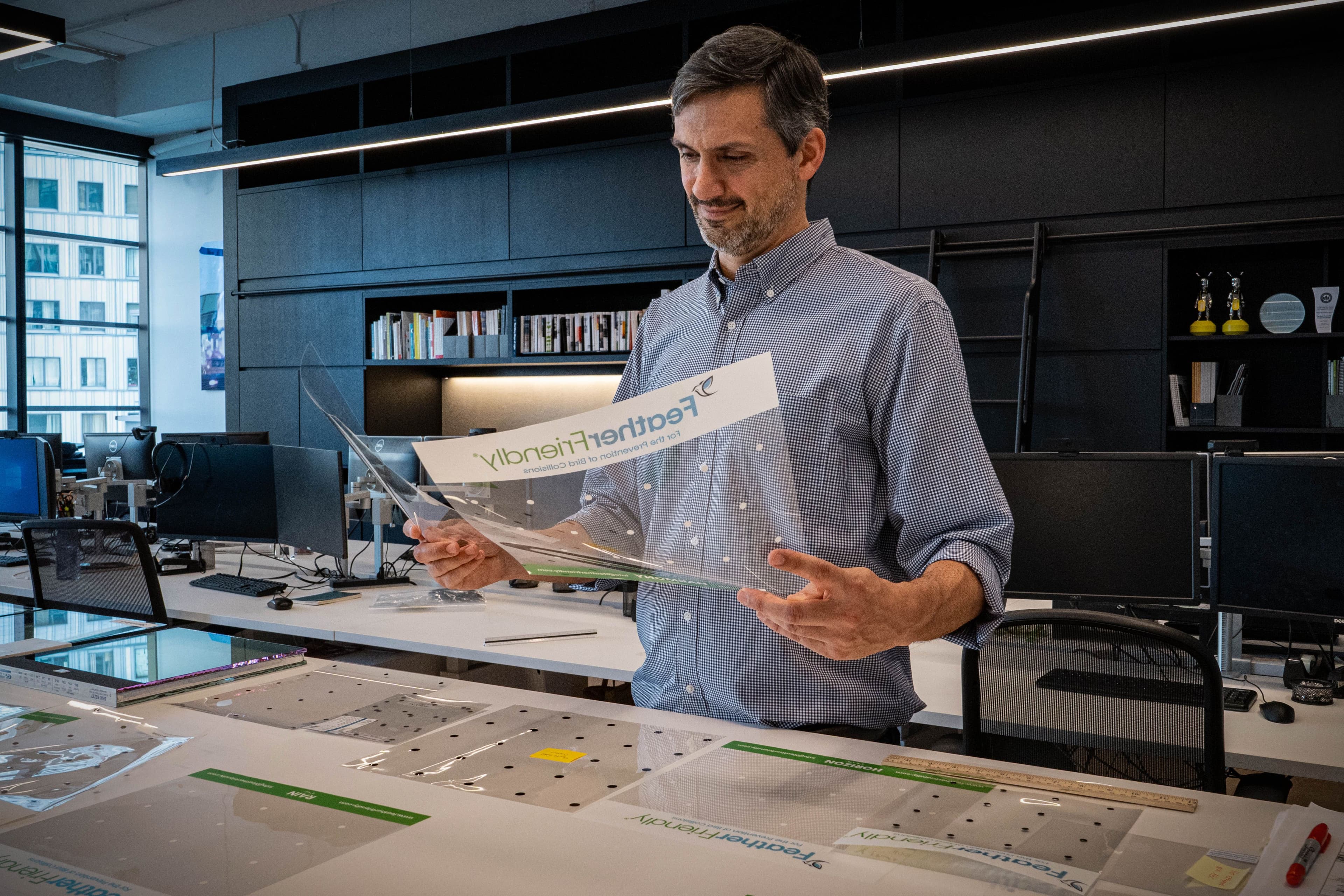

Collisions

Ranked third among U.S. cities for exposure to anthropogenic light at night—following Chicago and Houston—Dallas poses a significant risk to migrating birds (Bright Lights in the Big Cities: Migratory Birds’ Exposure to Artificial Light, 2019). Situated along the Central Flyway, Dallas sees millions of birds pass through each migration season, emphasizing the urgent need for bird-friendly practices. The Lights Out Dallas! campaign—part of the statewide Lights Out Texas! initiative—encourages reducing non-essential lighting across the DFW metroplex to protect these migratory birds. In response to the Texas Conservation Alliance’s call for action, Dallas has made notable strides, with landmarks like Reunion Tower and The Hunt Building officially participating in Lights Out this spring. “Aiming to ensure a darker night sky, all business owners and residents are encouraged,” explains the Texas Conservation Alliance. By adopting bird-friendly practices, Dallas is taking meaningful steps toward ensuring safer migratory journeys for countless birds each year.

Collision Monitors at Dawn: Omni Dallas Hotel

Texas Conservation Alliance member and Assistant Coordinator of Lights Out Dallas!, Heather Bullock (left), leads a team of volunteers during a 6 a.m. collision monitoring walk. From March 1 to June 9, 2024, the spring migration season, an estimated 1,312,174,000 birds have migrated through Texas. “We know that light pollution is extremely disruptive to birds who primarily migrate at night and use the stars to navigate,” says Bullock. “Light pollution causes them to not see those stars—they lose their map. So they come down lower to try to find their way by physiography. And when they do, they’re in great danger of colliding with human-made structures.”

Dallas, TX

The Magnolia at Dawn

Older buildings, such as this one, often pose less risk to birds due to their less-reflective design; however, all structures play a role in urban bird safety. To better understand bird building interactions, collision monitoring has become a crucial component of the Lights Out Texas campaign. While the campaign’s primary focus is to reduce light pollution during peak migration seasons to prevent bird disorientation, collision monitoring provides essential data that highlights the need for these protective measures.

Dallas, TX

Deceased Lincoln's Sparrow

A deceased Lincoln's Sparrow (Melospiza lincolnii) lies beneath the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center skywalk, one of many casualties recorded along the collision monitoring route. Collision monitoring involves early morning walks by volunteers, especially during peak migration seasons that occur each spring and fall, to identify and document birds that have struck buildings overnight, providing valuable data on how urban structures impact migratory species. Initially, Tim Brys from the Perot Museum of Nature and Science and Ben Jones from the Dallas Zoo mapped out hotspots across downtown, gradually adding buildings to the survey based on observations and expert insights. Today, the collision monitoring teams cover a 7-mile route spanning 23 buildings, gathering data to advocate for bird-friendly urban design and reduce these preventable collisions.

Dallas, TX

“A year or two ago, a photo went up on Reddit showing a lineup of birds in front of a building. I think it was in Houston—someone from Houston Audubon had spoken to the facilities and grounds staff to explain what they were doing. So, before the survey crew arrives, the staff pick up the birds and arrange them in a neat line, which looked really odd to passersby. Someone took a photo, posted it on Reddit, and it sparked a discussion about Lights Out. It was pretty cool.”

Collision Specimen at Dawn

Heather Bullock and Lights Out Dallas! intern Brendon Williams walk their portion of the collision monitoring route, checking behind barricades and shrubs and pausing at large windows where bird strikes are common. Although they initially find no casualties, they approach the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center—a known hotspot. "The Convention Center is the worst collision source in downtown Dallas. Over a quarter of all collisions we’ve recorded since the start of Lights Out Dallas! have happened here," Bullock explains. Soon after, they find a deceased Lincoln's Sparrow (Melospiza lincolnii) near a large meeting room window. They document the scene, label the bag “Convention Center Stairway,” and store the bird for data collection. “The Convention Center is being renovated, and Texas Conservation Alliance has reached out to the architects involved,” Bullock adds, noting this as a prime opportunity to install bird-friendly designs. So far, there has been no progress.

Dallas, TX

Skybridge at Dawn

The Skywalk, or “Skybridge,” connects the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center to the Omni Dallas Hotel. Built in 2011, the Omni’s untreated glass poses a serious threat to migratory birds. Dallas is not alone in facing this issue; Chicago’s McCormick Place Convention Center has become notorious for large-scale bird collisions, with nearly 1,000 birds striking the building in a single night during the fall of 2023. A study published in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on McCormick Place found that "reducing lighted window areas could lower bird mortality by about 60%." Since October 2023, McCormick Place has begun lowering window shades nightly, following recommendations from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. New York’s Javits Convention Center saw similar success, achieving a "90% collision reduction after implementing bird-friendly measures in 2013," according to the National Audubon Society.

Dallas, TX

Heather Bullock and Skybridge

Bullock stands beside the back of the convention center skywalk, wearing a volunteer leader vest and pin. Though not entirely made of glass, this part of the structure still poses a significant hazard for birds. According to the National Audubon Society, “internal plants near windows, glass corners, and greenery close to buildings can all be deadly as birds are unable to distinguish reflection from open flyway.”

Dallas, TX

Collision Monitors Collecting Data

After the survey route is completed, volunteers gather around Tim Brys’s truck, preparing to document the morning’s findings for Lights Out Dallas! Brys distributes clipboards, specimen tags, and the bird log binder, instructing volunteers to record details like species, location, and casualty ID. Each entry is logged both physically and in an online database, iNaturalist, where the data remains accessible to researchers and the public. Occasionally, the team finds birds that can still manage to be saved, "Stunned and injured birds get taken to Rogers Wildlife Rehabilitation Center for 'repairs' and hopefully are hopefully re-released," says Brys.

Dallas, TX

Tim Brys and Specimen

Brys holds the collection of birds documented on April 22, 2024. “We wanted this information to stay open source, where it was transparent,” says Brys. “There’s actually a number of people that pull data from that information, including the city of Dallas.” The iNaturalist entries help researchers map collision sites, offering valuable insights into patterns and hotspots across the city.

Dallas, TX

Tim Brys and Specimen

Tim Brys stands in front of a freezer in the Perot Museum’s teaching collection, where the deceased birds are temporarily stored. "All the deceased birds get frozen individually with their respective data tag that matches their iNaturalist entry," Brys states adding, "Birds get saved until either someone is traveling to College Station or until a full freezer creates need for an extra trip down. Drop-offs are all loaded into a giant cooler filled with bags of ice for the drive down."

Dallas, TX

Mei Leng Liu and Specimen

Since taking on a leading role with Lights Out Dallas!, the Texas Conservation Alliance has expanded its mission beyond collision monitoring to include education and community engagement. "We’re working with teachers to develop a Lights Out Texas! curriculum for 7th and 8th grade, though it’s still in progress," explains Mei Ling Liu, Texas Conservation Alliance's Community Conservation Director. "An Austin team from Defenders of Wildlife and Travis Audubon has created a curriculum for 3rd to 5th grade, currently in testing. In the future, we hope to encourage older students to advocate for change by reaching out to city officials, writing letters to mayors or councils, and promoting Lights Out initiatives in their communities."

Dallas, TX

Wing of Documented Specimen

When asked about the growing impact of Lights Out Texas!, Tim Brys shares how the initiative is expanding beyond Dallas: “We had someone reach out who used to work with us on the project here in Dallas. She’s now in Austin with Defenders of Wildlife and asked for help. It’s kind of spreading out.” Bullock emphasizes that collaboration among scientists, citizen scientists, and community enthusiasts forms the backbone of the program. “We know what the problem is. We know what the solution is,” she says. “The biggest thing is just raising awareness. Our role is to spread the word, inviting people to stand with us to protect these birds that are essential to our ecosystem.”

Dallas, TX

11-year-old Arjun Jenigiri and his mother, Radhika Lekkala, share over Zoom how Arjun became the youngest member of Lights Out Dallas!. Arjun's journey began when he first learned about Lights Out! through NPR, and later connected with Tim Brys of the Perot Museum. "I felt like a hero." His commitment to conservation runs deep: "I feel like any creature's life is as important as a human life." Together, Arjun and his mother continue to advocate for change by placing Lights Out! signs in their yard during peak migration months. Through his dedication, Arjun hopes to inspire others and create a brighter future for migratory birds.

Irving, TX

Collisions Research

College Station, Texas, serves as the next destination for bird specimens collected through the Lights Out! Program. Heather Prestridge, curator at the Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections in Texas A&M University's Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, leads volunteers in the preservation process. Many of these specimens will contribute to ongoing scientific research, providing valuable DNA and other materials for studies in ecology, conservation, and evolutionary biology.

Heather Prestridge and Specimen Cabinet

Heather Prestridge organizes preserved Common Yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas) in a drawer in one of the many cabinets that store specimens collected throughout the years at the lab. Dallas isn't the only location that the lab collects collision monitoring samples from. "Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Galveston, Fort Worth. They spend a little bit of time in our freezer, and we rely on a volunteer crew of students to prepare the specimens to our museum standards," says Prestridge.

College Station, TX

Specimen Cabinet: Closer Look

Prestridge opens another drawer, revealing a variety of bird specimens, each of which migrates through Texas. "The gold standard for museum specimens is to retain all diagnostic characteristics," she explains. "Birds are identified by plumage, which is why we preserve the skin. Our specimens hold significant value because we can record mass, measurements, reproductive condition, age, and body condition. All of these data points are cataloged in our database, linked to each specimen, enhancing their scientific utility."

College Station, TX

Pinned Specimen

Prestridge's hand reaches toward the pinned bird specimens arranged on a foam board, each tagged and meticulously organized for study. The yellow pins hold the birds in place, allowing researchers to examine features like plumage, body condition, and other physical characteristics as part of ongoing research. "We take the skeleton and all of the insides out of the bird, so you're left with just the skin," Prestridge explains. "The skin is filled with cotton and then carefully sewn shut, so it’s still a floppy piece of empty bird. Pinning them onto the board allows them to dry in a really neat fashion... they'll be sturdy for a long time. Once it's dry, you can't go back and change it."

College Station, TX

Spread Sparrow Wings

A close-up of labeled bird wing specimens, carefully tied and stored for study. "Spread wings are important too, because you can't spread the wing of a prepared bird specimen," says Prestridge. The preserved wings, tagged with identification numbers, allow researchers to examine molt patterns, age, and other morphological details without needing a full specimen. "When we get, say, 109 white-throated sparrows from Dallas in a season, we sort through them and decide to turn some into spread-wing specimens. The spread wings are quicker to prepare. They also serve as good training for newcomers to specimen preparation, helping them understand how delicate the process is."

College Station, TX

Frozen Tissue Samples

A frozen storage unit houses rows of meticulously organized drawers filled with preserved bird samples, each carefully labeled and cataloged. These samples, collected as part of Texas A&M’s biodiversity efforts, are invaluable for both research and collaboration. "We've spent a lot of time collaborating with other colleagues here at Texas A&M but also UT San Antonio, and a couple other universities," says Heather Prestridge. "The Lights Out! birds... provide a large sample size in a small amount of time." These specimens have allowed researchers to explore a variety of pressing issues, from avian influenza and avian Borna virus to the presence of microplastics in bird populations. "We here at our collections save a tissue sample, typically a piece of heart and a piece of breast tissue... data are shared for those alongside the specimens, for anyone who wants to use the data or wants to request tissue samples," she adds, emphasizing the usability of the samples. "We believe our collections will endure indefinitely, as our primary focus is documenting biodiversity across space and time," Prestridge concludes. The specimens provide valuable insights into ecological changes of the past, present, and future.

College Station, TX

“Salvage birds are important. Before Lights Out!, we sometimes had an empty freezer. For anyone starting a collision monitoring program, the first step is to connect with a collection. If a specimen isn’t saved, it has no use, right?”

Policy

Policy is a key tool in addressing bird conservation challenges. As Glass Coalition Program Coordinator at the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Kaitlyn Parkins explains, "The American Bird Conservancy has taken the stance that policy is the best way to address window collisions." New York has taken a leading role with laws like Local Law 15, which mandates bird-friendly building materials, alongside measures addressing light pollution. Texas, on the other hand, has focused on proclamations—symbolic gestures that, while raising awareness, lack the enforceable power of legislation. Meaningful progress often starts with individuals. In New York City, Kathy Nazari of the Lights Out Coalition helped pass key laws requiring bird-friendly construction and reduced nighttime lighting. Meanwhile, in Texas, high schooler Diya Balagopal campaigned to adopt a Lights Out proclamation in Frisco, showcasing the power of individual advocacy.

Diya Balagopal (16) from Frisco, TX, shares over Zoom how a personal experience during quarantine led her to champion conservation efforts and raise awareness about bird migration and light pollution. Recognizing the critical role Texas plays as a migratory pathway, Diya noticed that the public wasn’t unwilling to help but simply unaware of the issue. "When we really told people, we saw they connected with it," she explains. Determined to make a difference, she attended multiple city meetings, delivering speeches about bird migration, collisions, and the importance of Lights Out! nights. The result: a successful campaign for a Lights Out! proclamation in Frisco, Texas. Her work not only highlights the power of youth in driving meaningful environmental change but also underscores how accessible policymaking can be.

Frisco, TX

Kathy Nizzari and Campaign Posters

Kathy Nizzari, founder of the Lights Out Coalition, sits in front of posters from past advocacy campaigns. The coalition, dedicated to protecting urban wildlife, focuses on reducing bird deaths caused by building collisions through advocacy, education, and legislative action. The coalition was fundamental in passing Local Laws 30 and 31, requiring city-owned buildings to turn off unnecessary lights at night and use motion sensors. Now, Nizzari is advocating for two new bills: one to retrofit existing buildings with bird-safe glass in the first 75 feet and another to mandate privately-owned buildings turn off lights after hours. “New York City’s building collisions alone are responsible for roughly a quarter of a million bird deaths every year,” she explains. Despite pushback from the real estate industry, Nizzari remains focused. “When you save animals, you’re protecting the environment and human health—and vice versa,” she says. Looking ahead, she plans to expand her efforts nationwide, helping other cities adopt similar legislation.

New York, NY

Glass Research

"Lights Out Chapter two is about glass," observes Heather Prestridge. While the first chapter focused on reducing light pollution to prevent bird collisions, the secondary effort now addresses the role of glass. The American Bird Conservancy (ABC) operates two dedicated testing sites to evaluate glass and other materials for their ability to deter collisions. The first site, located at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Avian Research Center in Rector, Pennsylvania, has long been a cornerstone of this work.

Flight Tunnel at Powdermill

The Powdermill Avian Research Center’s flight tunnel, developed with the American Bird Conservancy, allows researchers to study bird behavior around various window treatments. Birds from the center's banding program briefly participate in controlled flights toward two panes with different materials, helping assess bird-safe glass options. "American Bird Conservancy, and Dr. Christine Shepherd," Anikó Tótha explains, "adopted the glass testing tunnel over 10 years ago. Our two tunnels are based on the first built in Hogan, Austria, which tests transmission. [These] are the two tunnels we have now, one at Powder Mill and the second at Forman Branch Bird Observatory affiliated with Washington College."

Rector, PA

At the Powdermill Avian Research Center, researchers use a specialized flight tunnel to study how birds perceive glass. The work is part of an effort to develop bird-friendly window treatments that reduce the risk of collisions.

Yellow Warbler and Safety Net

A bird safely makes contact with a net inside the flight tunnel at Powdermill Avian Research Center. This controlled setup allows researchers to test and identify effective bird-safe glass solutions to help reduce collisions in real-world environments.

Rector, PA

“Share your passion for birds with others, because it can be infectious.”

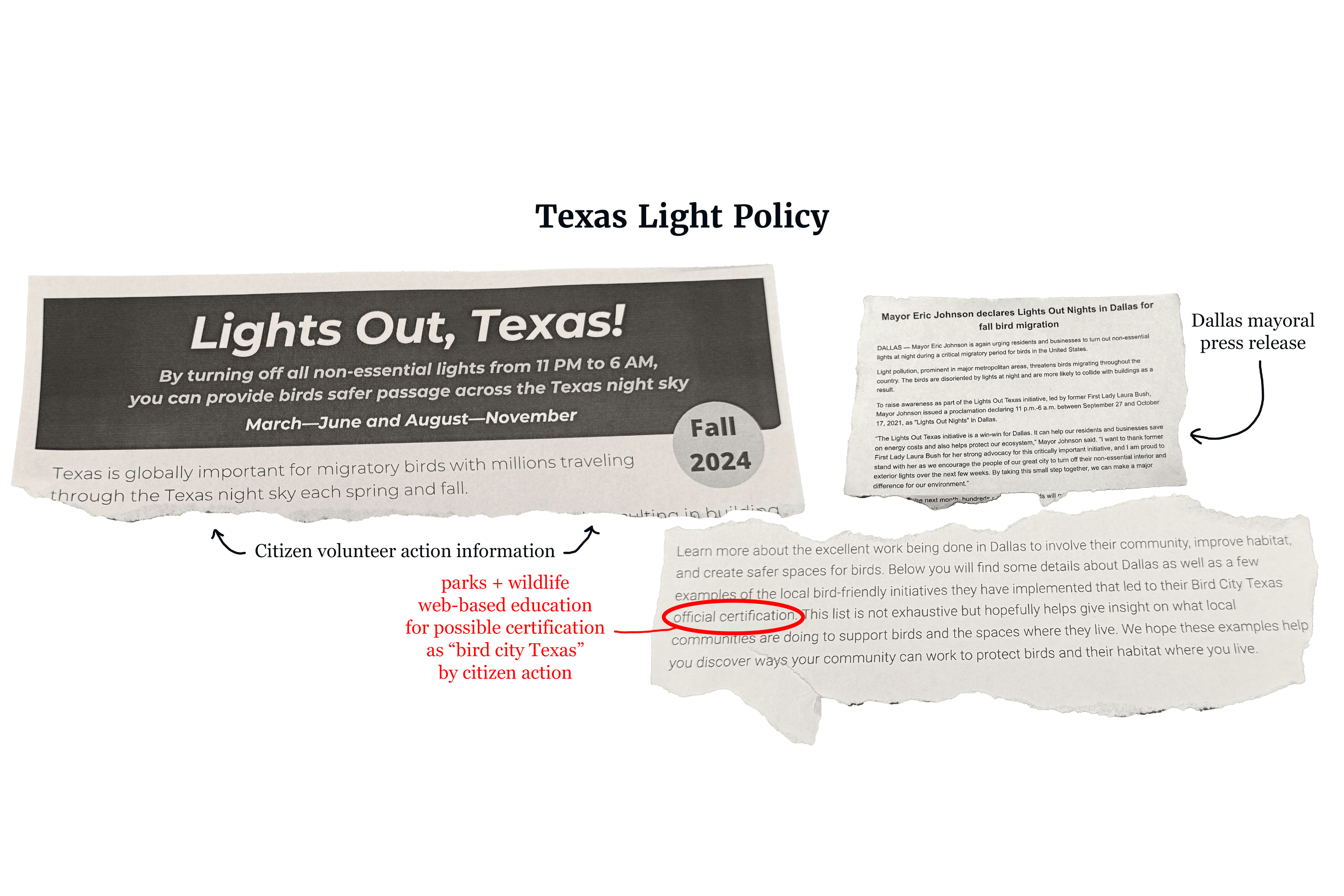

Architecture

With the implementation of Local Law 15 of 2020, New York City has emerged as a leader in advancing architectural practices that prioritize bird safety. The law mandates the use of bird-friendly materials in new construction and major renovations, requiring features like UV coatings and frit patterns to make glass visible to birds. Dan Piselli, Director of Sustainability, notes, “Our approach is to show clients all of the available options and discuss each with them. Some clients prioritize cost, others prioritize view clarity, others different factors. NYC projects must comply with our bird-friendly building law...” This approach emphasizes thoughtful design to balance compliance with client needs. Projects like 1 Java Street in Brooklyn and FXCollaborative’s retrofits demonstrate how architects are addressing these challenges, reducing collisions while improving energy efficiency, privacy, and overall sustainability.

Dan Piselli and Window Decals

Dan Piselli, Director of Sustainability at FXCollaborative Architects, examines bird-friendly decals applied to his office building's glass façade in New York, NY. These decals were installed after observing bird collisions near the 7th-floor terrace, which faces neighboring green roofs. The retrofit uses a proven collision-mitigation product that balances bird safety with maintaining clear views and daylight. "Bird-friendly glazing is a rare example of a material with a very direct effect, literally saving the lives of birds every day," Piselli stated, highlighting the immediate impact of sustainable design choices. "It’s clear that human impact on Earth is devastating the ability of life to continue," he added in an email, underscoring the importance of integrating sustainability into architecture.

New York, NY

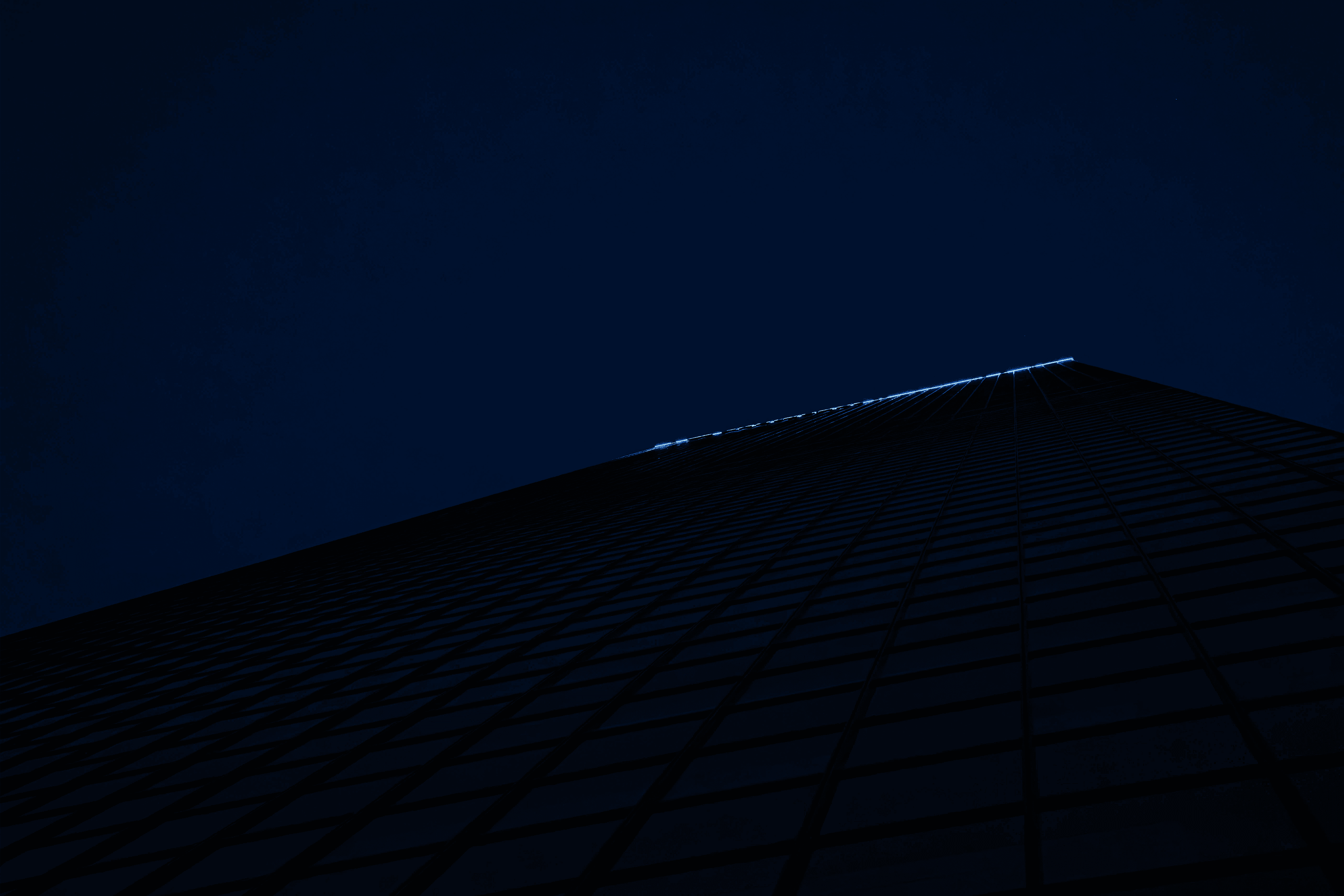

Ceramic Frit Pattern

A close-up view of bird-friendly glazing, often implemented into building designs by architects at FXCollaborative, highlights the intricate patterns designed to prevent collisions. "There are a number of available technologies to mitigate bird collisions with glass in new buildings," Dan Piselli states. "Each can be applied to make patterns on the glass that birds can see. Technologies include ceramic frit, which is baked onto the surface of glass, etching achieved with lasers or acid application, and UV-reflective coatings."

New York, NY

1 Java Street

Efforts to incorporate sustainability and bird-friendly design are gaining traction across various architectural firms. 1 Java Street, a prime example of bird-friendly solutions in action, rises along Brooklyn's Greenpoint waterfront as a new construction project designed with bird-friendly Guardian Glass to help prevent bird collisions. This building is part of New York City's commitment to environmentally conscious construction through Local Law 15. The project features Guardian Glass with a bird-friendly coating on all windows and storefronts up to 75 feet above grade, in accordance with the NYC Building Code. This accounts for approximately 50% of the glass used in the project. The installed glass is UV-treated, similar to the glass being tested at Powdermill, and is intended to deter birds.

New York, NY

1 Java Street

A closer look at the bird-friendly glass materials used at 1 Java Street reveals that the UV patterns become faintly visible to humans due to the angle of reflection at sunset. While this effect is only noticeable to humans during such conditions, the UV-reactive materials are theoretically always visible to birds, ensuring consistent deterrence and protection throughout the day.

New York, NY

Dan Piselli and Installed Decals

Today’s bird-friendly architecture seamlessly merges conservation with design, creating spaces that prioritize both ecological preservation and human experience. At the Columbia School of Nursing, translucent frit patterns on private room windows stand as a compelling example of this. "The frit was primarily used to provide privacy for students and faculty. In addition, the frit helps mitigate bird collisions, reduce glare onto the street, and reduce solar heat gain to reduce air conditioning loads," Dan Piselli explains. By integrating sustainability with aesthetics and functionality bird-friendly architecture can not only address environmental needs but also enhance a space's overall experience.

New York, NY

Enthusiasts

Bird enthusiasts are often the unnoticed change-makers in environmentalism, quietly championing small yet impactful actions that create meaningful change. Their dedication stems from a profound appreciation for the beauty and resilience of birds, coupled with a commitment to their survival amidst modern threats. Sally Alhadeff, a lifelong bird lover from Washington State, illustrates this passion with her reflections on the migration of House Wrens. “Here’s this little tiny bird that’s one of the world’s worst flyers... and this bird is totally dependent on going from backyard to backyard... small things make a huge difference to birds,” she explains. Bird enthusiasts lead by example, and in a world often focused on large-scale solutions, these devoted individuals remind us that small gestures are not just contributions—they are the cornerstones of change.

Eliza Wein at Lab of Ornithology Open House

Eliza Wein, a senior at Cornell University studying Environment and Sustainability, sits quietly outside the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. For Wein and many like her, appreciation for birds is more than a hobby—it’s the first step toward environmental action. A dedicated member of "Birding Club Cornell," Wein has worked hard to protect birds on campus. “There’s a group of students on the Cornell campus... called Cornell Dead Bird Alert,” she explains. “When there’s a dead bird on campus that’s collided with a window, we report it to that group. I think we’re probably the only college that does that.” “People love what they know,” she reflects. “If you get someone to love birds, you’re making a conservationist right there.”

Ithaca, NY

Swarovski Spotting Scope

The best way to appreciate birds has traditionally been with binoculars. Depicted here is a "spotting scope." While binoculars offer a wider view, a spotting scope provides higher magnification. Modern technology is introducing new ways to enjoy birding. Apps like Merlin, developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, help identify birds by sight and sound, making birding accessible to those who might not have considered it before. “My friend, who’s a computer science major, didn’t care about birds before, but now he’s really into birding—largely because of Merlin. Apps like Merlin bring birding to the masses, making it accessible to people who wouldn’t otherwise care about birds,” says Eliza Wein.

High Island, TX

Leo and Brooke at Dawn

Leo Gilman, an Environment and Sustainability major with a Humanities Concentration at Cornell University, stands on the roadside using the Merlin Bird ID app to identify birds by their calls and movements. "Phones are so useful for birding, so I use mine a lot," Gilman explains. “Merlin is incredible—it makes birding accessible to anyone. You can identify birds by sound, by sight, or even from a photo. It’s just so convenient.” As a Student Worker Level II at Birds of the World, Gilman has worked on copyediting and managing tables, photos, and maps for the publication. He emphasizes how technology has revolutionized birding. “I rarely take a camera with me, because so often I focus more on the photo than watching what’s in front of me. Apps like Merlin let you engage with the birds in real-time without needing expensive equipment.” For Gilman, birding is about connection. “You just need to be out there, looking at or hearing birds in whatever way you want. Merlin makes that so much easier for everyone.”

Sapsucker Woods Sanctuary, Ithaca, NY

Wetlands in High Island

This wetland in High Island, Texas, covered in green vegetation and surrounded by bald cypress trees, serves as a critical stopover point for migratory birds flying over the Gulf of Mexico. It provides food, shelter, and rest along their journey. Conservation efforts by birding enthusiasts and environmentalists help keep these habitats as safe havens for birds during their seasonal migrations.

High Island, TX

Golden-Wing Society at High Island Beachfront

Members of Cornell's Golden Wing Society gather in High Island, Texas, for a week-long birding trip with Victor Emanuel Nature Tours. Among them is Sally Alhadeff, a dedicated bird watcher since the 1970s, who reflects, “Birds are more than just background noise—they add a richness to our world that we can't replace. Protecting them is crucial.”

High Island, TX

“Once you get into it a little bit, you start birding everywhere— you start watching birds when you’re walking to and from things, when you’re driving, and everything in between.”

The Bottom Line

The development of Blinded Flight was driven by a striking statistic published in 2014 estimating 365 to 988 million birds die annually in the U.S. due to building collisions.

Research conducted during the development of this project suggests this figure now exceeds one billion birds annually (PLoS ONE, 2024), reemphasizing the pressing need for action. Blinded Flight aims to inspire change by uniting environmental science, policy, advocacy, architecture, and public enthusiasm to address light pollution and bird-building collisions. Solutions like dimming lights, adopting bird-friendly designs, and fostering awareness provide practical ways to mitigate this crisis. Greater investment in avian research and conservation can drive further progress.

About The Author

Ania Johnston is a Polish-American multimedia journalist specializing in visual storytelling and global issues. Her work explores the intersections of climate change, technology, and human narratives, with projects spanning Europe and the United States. Fluent in Polish and English, Ania has lived and worked in Poland and the Czech Republic, bringing a diverse perspective to her reporting. She holds a Master of Science in Multimedia, Photography, and Design from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and a Bachelor of Arts in Film with a concentration in Cinematography from Syracuse University.

Further Resources

With a clearer understanding of the intersection between light pollution, building design, and bird migration, you are empowered to act. Explore these resources to join the effort:

Bird-Building Collision Prevention

- FLAP (Canada)

www.flap.org - American Bird Conservancy: Glass Collisions

abcbirds.org - BirdSafe (Canada)

www.birdsafe.ca - NYC Bird Alliance: Make Your Windows Bird-Friendly

www.nycbirdalliance.org - NYC Bird Alliance

www.nycbirdalliance.org

Lights Out Initiatives

- Lights Out! Programs

www.audubon.org/conservation/project/lights-out - National Audubon Society: Lights Out www.audubon.org/conservation/project/lights-out

- Lights Out Connecticut: Model Municipal Lighting Policy

www.lightsoutct.org - Lights Out DFW (Texas Conservation Alliance):

www.tcatexas.org/lights-out-dfw - BirdCast: Here's How You Can Make a Difference

birdcast.info

Light Pollution Reduction

- International Dark-Sky Association

www.darksky.org - International Dark-Sky Association: Policy Templates

www.darksky.org - Aeroeco Lab: U.S. Lights at Night

aeroecolab.com/uslights

Research

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

www.birds.cornell.edu - American Ornithological Society

americanornithology.org - BirdLife International

www.birdlife.org - eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

ebird.org - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Migratory Birds Program

www.fws.gov/program/migratory-birds